The Limits of Ground-Based Testing

Wind tunnels have been a cornerstone of aerospace engineering for over a century. From early propeller-driven aircraft to today’s sleek supersonic jets, wind tunnels allow engineers to test and refine designs in a controlled environment. But as we push into the realm of hypersonic flight—where vehicles travel at Mach 5 or faster—the limitations of wind tunnels become more apparent. In particular, when it comes to high-altitude plasmas, wind tunnels simply can’t replicate the full story.

At speeds and altitudes typical of hypersonic flight, the atmosphere behaves in complex and extreme ways. The air around a vehicle doesn’t just heat up—it begins to ionize, forming weakly ionized plasmas. These plasmas influence the vehicle’s aerodynamics, heat transfer, and even electromagnetic properties. And while wind tunnels can simulate high-speed flow and heating to some degree, they struggle to accurately replicate the thermochemical nonequilibrium and plasma effects seen in real high-altitude flight.

What Is a High-Altitude Plasma?

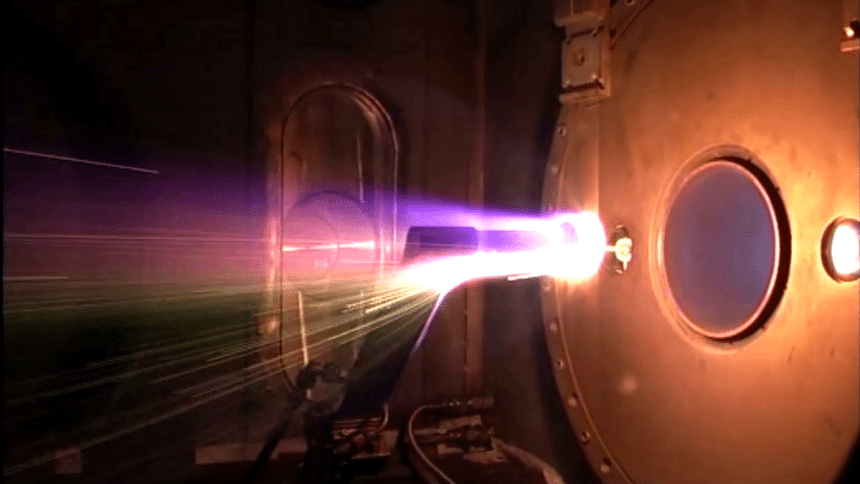

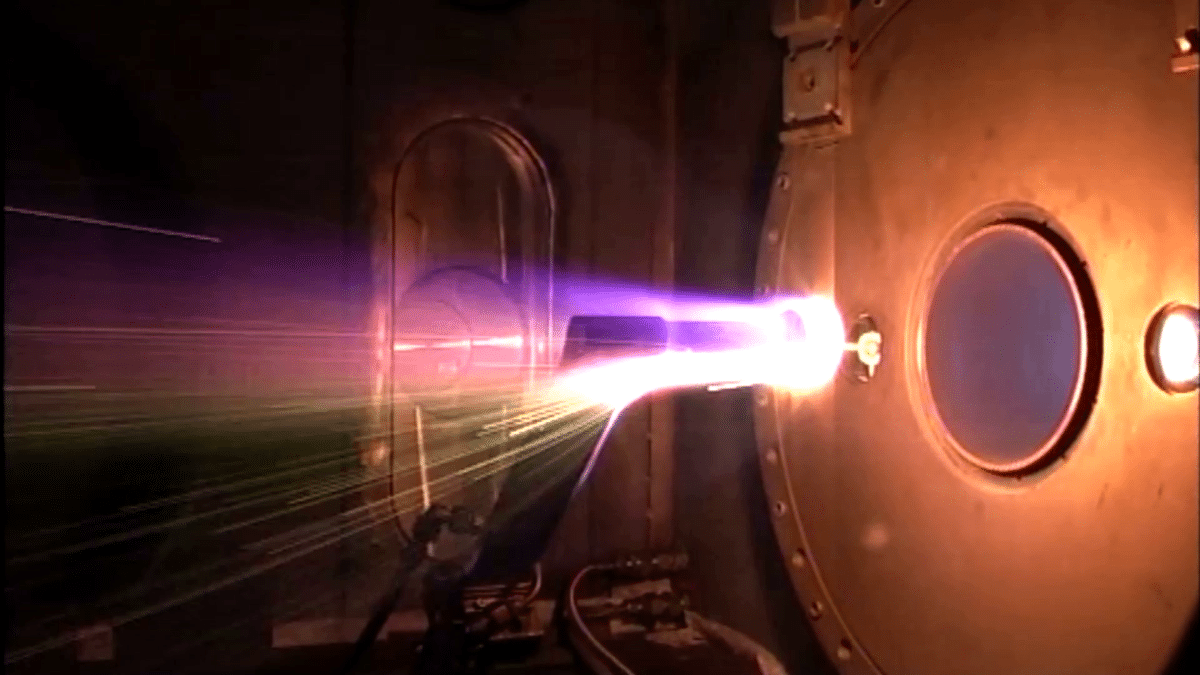

In everyday life, plasma might make you think of neon signs or lightning. But in high-altitude hypersonic flight, plasma forms when air molecules are heated to extreme temperatures—often over 5,000 Kelvin—and start to break apart into ions and electrons. This occurs most intensely in the shock layer that forms in front of a fast-moving vehicle, especially during reentry or high-speed cruise at the edge of the atmosphere.

This plasma isn’t fully ionized, like in a fusion reactor; it’s weakly ionized, meaning that only a small fraction of the air molecules are ionized. However, even this small amount can have significant effects on vehicle performance, communication systems, and thermal protection systems.

The Problem with Wind Tunnels

So why can’t wind tunnels capture all these effects? The main reason is that ground-based facilities operate under very different conditions than those found at high altitudes. Most wind tunnels test at near sea-level pressures, which allows them to simulate high-speed flow by compressing air and accelerating it over a model. But at altitudes of 50 kilometers and above, where many hypersonic vehicles operate, air density is extremely low.

To simulate these conditions on the ground, engineers use vacuum facilities or shock tunnels, which can briefly achieve low pressures and high temperatures. However, these setups have severe time limitations—often lasting only milliseconds—and struggle to accurately simulate the full range of chemical reactions and ionization processes happening in flight.

Moreover, plasmas in high-altitude flight are affected by background radiation, long-duration flow, and ambient magnetic fields, none of which are easily replicated in a lab. This creates a gap between what we can measure on Earth and what actually happens during flight.

Missing the Mark on Nonequilibrium Chemistry

One of the most critical issues is thermochemical nonequilibrium—a condition where different parts of the air molecule population (translational, rotational, vibrational, and electronic modes) have different temperatures. In hypersonic flight, air molecules may be moving very fast (high translational temperature), but their internal vibrations and electronic states lag behind. This directly affects how quickly molecules break apart (dissociate) and ionize, which in turn impacts how plasma forms and behaves.

Wind tunnels typically cannot sustain these nonequilibrium conditions long enough to fully capture the kinetic processes at play. The result is that models and data based solely on wind tunnel tests may overestimate or underestimate ionization levels, leading to inaccurate predictions of heating, drag, and electromagnetic interference.

Researchers like Sergey Macheret have emphasized the need for advanced numerical simulations to complement wind tunnel testing. These simulations incorporate detailed multi-temperature models and plasma kinetics to predict how the flow evolves in actual flight conditions. Only by combining experimental data with these sophisticated models can we begin to fill the knowledge gap.

Why It Matters for Design and Safety

Understanding high-altitude plasma effects isn’t just an academic exercise—it has real-world implications. For example, during atmospheric reentry, plasma can block radio communications in a phenomenon known as blackout. Engineers need accurate models of plasma formation to design communication systems that can penetrate or work around this barrier.

Additionally, the presence of plasma affects heat transfer to the vehicle surface. Incomplete modeling of plasma behavior can lead to under-designed thermal protection systems, risking vehicle damage or mission failure. And for concepts like magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flow control, where magnetic fields interact with plasma to modify airflow, predicting plasma conductivity accurately is critical.

As hypersonic vehicles become more common, including those for defense and commercial applications, these plasma-related design challenges must be solved with confidence. Relying solely on wind tunnel data could lead to costly mistakes or overly conservative designs.

Toward a More Complete Approach

The future of hypersonic flight demands a more integrated approach to plasma research. This means improving wind tunnel capabilities, but also investing in flight experiments and advanced simulations. Initiatives to develop plasma diagnostics, including optical and microwave-based sensors, are helping researchers measure plasma properties in real-time during ground and flight tests.

Experts like Sergey Macheret advocate for a hybrid strategy, combining empirical data, high-fidelity modeling, and novel diagnostic tools to bridge the gap between lab conditions and real flight. Only by understanding what wind tunnels can’t tell us—and finding ways to fill those gaps—can we safely and effectively navigate the plasma-laden frontier of hypersonic flight.